Blaine Amendments: An Overview for Religious Educators

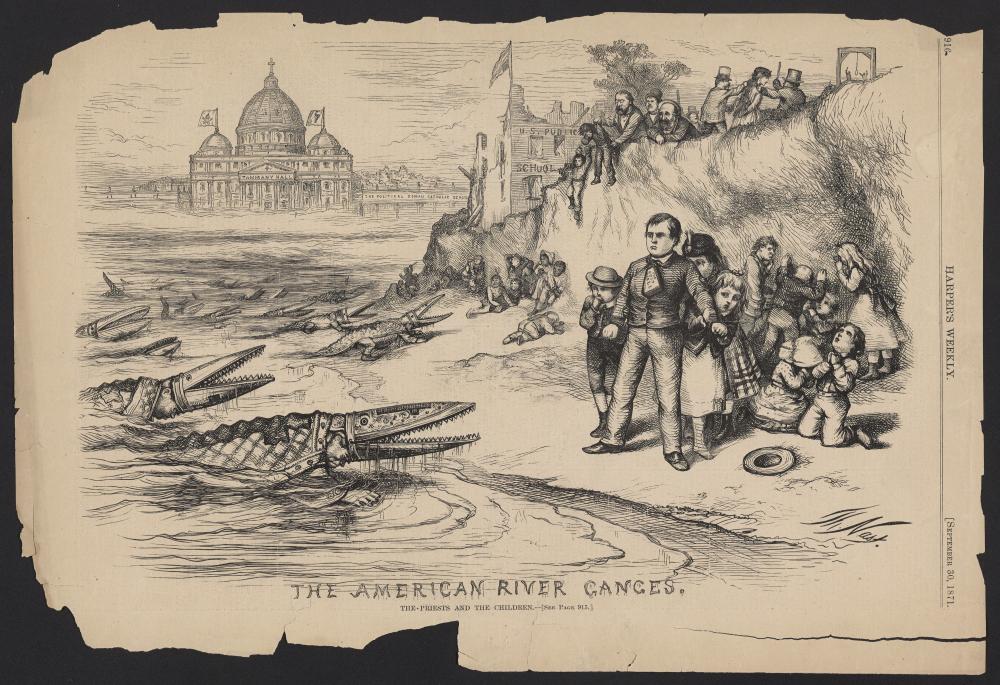

Photo credit: Thomas Nast, “The American River Ganges. The priests and the children,” Harper’s Weekly (Sept. 30, 1871), source: https://omeka.chrc-phila.org/items/show/7357.

“Blaine amendments” are provisions in many state constitutions that prohibit religious schools (and sometimes other religious institutions) from accessing public funds. Significantly for religious educators today, nearly every Blaine amendment is unconstitutional. The Supreme Court has confirmed through a series of cases, most recently Carson v. Makin,1 that a state may not exclude religious entities from participating in otherwise available government programs.

Even so, many states maintain unchallenged Blaine amendments, and a religious school that seeks to participate in a public funding program in an untested Blaine state may face litigation despite the recent Supreme Court precedent. But the Blaine era appears to have reached its end, and it comes as Americans are primed for a sea change in education policy: public school enrollment and academic performance are in decline, private school enrollment has climbed, and homeschooling is booming. In 2023 alone, twenty states expanded their school choice programs. By the start of the 2026–27 school year, at least sixteen states are slated to have universal school choice in place. Public funding of religious schools is now a viable political opportunity in America.

A Short History

Blaine amendments “cannot be fully understood without reference to the irreducibly anti-Catholic ideology that inspired and sustained them.”2 Distrust of Rome is native to the United States—a nation whose philosophical and theological wellspring is Enlightenment-era thought. Many early Americans saw the Catholic Church as an adversary. As Professor Richard W. Garnett has put it, American anti-Catholicism “arrived on the Mayflower.”3

In the late nineteenth century, millions of Catholic immigrants arrived on America’s shores, and America’s deep-seated fear of Catholicism reared its ugly head in response. A faction of Americans sought to stifle Catholic influence in the United States, especially the influence of Catholic education. After all, Catholic immigration meant that Catholic institutions would assume greater prominence in American life. And Catholics were a “sect” particularly concerned with the education of their children in the faith. Hence the trouble of the Catholic school. Nineteenth-century Americans applied the derogatory label “sectarian” to Catholic schools to highlight their perceived divisive identity.

For nineteenth-century Protestants, Catholic allegiance to the Pope called into question the possibility of Catholic allegiance to the United States. After all, Catholic doctrine binds the faithful to a certain obedience to the Holy Father—a foreign, absolute monarch who, until 1870, was sovereign of the Papal States and commander of a standing army. Thus, among other objections to the theology and culture that Catholics brought to the country, Americans questioned the civic loyalties of students educated in Catholic schools.

While Americans grappled with the issue of the Catholic immigrant, states busily went about erecting public school systems capable of providing near-universal education.4 These early government schools were effectively Protestant—featuring daily prayer, hymn singing, and Bible lessons.5 As Catholic schools grew alongside these public schools, the divide between “sectarian” and public education reached a head. How was a state—itself assuming a more significant role in the education of its young citizens—to deal with the considerable number of schools that educated Americans under the banner of Catholicism?

For many public officials, the fitting response to the Catholic problem was to put sectarian schools in a chokehold. Specifically, Congressman James G. Blaine of Maine proposed a national amendment to the U.S. Constitution to prohibit taxpayer money raised for the support of schools from coming “under the control of any religious sect.”

By starving sectarian institutions, Blaine and his supporters might diminish Catholic influence in American life. President Ulysses S. Grant supported the Blaine Amendment and pitched it not only as a defense against Rome, but also “pagan or atheistical tenets.”6 The Amendment passed the U.S. House of Representatives but narrowly failed in the Senate. Undismayed, Blaine and his supporters set to work enacting dozens of “baby Blaine” amendments at the state level to accomplish the same restrictions. In total, thirty-seven states enacted amendments that banned sectarian schools from receiving public funds.7

Consequences of the Blaine Approach

As a coincidence of history, Blaine amendments assured the failure of Congressman Blaine’s own project. What began in 1875 as Blaine’s rallying cry to preserve America’s religious character became, in the twentieth century, the very instrument by which state governments secured the false maxim of “separation of church and state.” Public schools steadily lost their religious character, and religious schools—whether Catholic or Protestant—were denied public funds.

Still, with virtually no public assistance, religious schools in the United States today serve more than 3.5 million students, including many from underserved communities.8

To be clear: the Blaine approach is an aberration on the global stage. While European nations almost universally subsidize religious schools (even the aggressively separationist France9), the United States shares company with the likes of Cuba and North Korea in its historical prohibition of public funding for religious entities. And secular states like those of Europe have good reason to fund these institutions: religious schools educate and form responsible citizens for the common good, often with greater success than their public counterparts.10

Constitutionality and the Path Forward

Whatever its motivations or effects, it appears that the death knell now tolls for the Blaine amendment. In 2017, the Supreme Court ruled 7-2 in Trinity Lutheran v. Comer that Missouri’s exclusion of churches from an otherwise neutral playground-related aid program was unconstitutional. Then in 2020, the Supreme Court held in Espinoza v. Montana that a state scholarship program that provided funds for students to attend private schools could not exclude religious schools. Most recently, in 2022, the Court ruled in Carson v. Makin that Maine’s “nonsectarian” requirement for an “otherwise generally available tuition assistance” program was unconstitutional.

In short, the U.S. Constitution does not permit a state to exclude religious schools from funds the state otherwise makes available to private schools. The anti-Catholic animus of the Blaine movement and the separationist intuitions of the twentieth century missed the mark. Blaine amendments are a dead letter.

Yet the death of Blaine amendments does not positively require states to fund private schools. Rather, the work of remedying America’s Blaine mindset has just begun. Litigation is a probable growing pain for trailblazing religious schools who seek public funds, and legislation to expand voucher programs and other forms of school choice is in order. Finally, religious educators should exercise prudence in accepting any public funds that are made available, keeping an eye toward undesirable conditions a state may attach to the funding.

-----------------------------

1 142 S. Ct. 1987 (2022).

2 Richard Garnett, Theology of the Blaine Amendments, 2 First Amend. L. Rev. 45, 62 (2004).

3 Id. at 63.

4 See The Center on Education Policy, “History and Evolution of Public Education in the US,” The George Washington University Graduate School of Education and Human Development (2020), available at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED606970.pdf.

5 See Erica Smith, “Blaine Amendments and the Unconstitutionality of Excluding Religious Options From School Choice Programs,” Federalist Soc. Rev. (Dec. 19, 2016), available at https://fedsoc.org/fedsoc-review/blaine-amendments-and-the-unconstitutionality-of-excluding-religious-options-from-school-choice-programs.

6 See Ulysses S. Grant, Remarks at the Ninth Annual Meeting of the Army of the Tennessee in Des Moines, Iowa (Sept. 29, 1875), available at https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/remarks-the-ninth-annual-meeting-the-army-the-tennessee-des-moines-iowa.

7 See generally, Kyle Duncan, Secularism’s Laws: State Blaine Amendments and Religious Persecution, 72 Fordham L. Rev. 493, 507–15 (2003).

8 See Ruth Graham, “Christian Schools Boom in a Revolt Against Curriculum and Pandemic Rules,” N.Y. Times (Oct. 19, 2021), available at https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/19/us/christian-schools-growth.html.

9 See Education Indicators: An International Perspective, “Sidebar: What is ‘public’ and ‘private’ education?” National Center for Education Statistics (Nov. 1996), available at https://nces.ed.gov/pubs/eiip/eiip45s1.asp.

10 See Emily Pierce and Cole Claybourn, “Private School vs. Public School,” U.S. News (Aug. 29, 2023), available at https://www.usnews.com/education/k12/articles/private-school-vs-public-school.

.png)